A quick recap, for those who’ve just joined us. In early 2019 I decided to watch all televised Doctor Who in order from the start: that took me until shortly before the broadcast of what is, at time of writing, the most recent episode, The Power of the Doctor, in the autumn of 2022. By then I had already started publishing my notes, originally written for a mailing list of nerds; but to maximise the chance of anyone reading the things I’d decided I’d publish those on the old (1963-89) and new (2005-) series in parallel. If you’re a regular reader, you’ll have noticed that I’ve just exhausted the old series. I have not exhausted the new.

But! I did not go straight from Survival, the last story of the old show, to Rose, the first of the new. I had to watch the 1996 TV movie, obviously; but I also decided to check out the 1993 30th anniversary charity “special” Dimensions in Time, a couple of radio plays, an ill-timed 2003 attempt to relaunch the show as an online cartoon staring Richard E. Grant... Anything, in fact, that felt like it had been intended by some part of the BBC or another to signal, “Look, Doctor Who’s back!”

Then I decided to go farther – partly because I wanted to try to trace some of the writers or ideas that would find their way into the new series back to their origin points in the wilderness years; partly, too, because the idea of only covering failed relaunches, many of which weren’t very good, depressed me. So I added to the list some of the most influential of the New Adventures novels, which had continued the story after Survival, and which had played a big part in my own fandom. Lastly, I added a couple of Big Finish audios, because even though they’re not that big a deal to me personally they were a huge part of the second interregnum, and remain a bit part of Who as a whole, and so it felt a bit off to skip them entirely.

All that, though, is still to come. First, perhaps the most influential Doctor Who story never shown on television. As in all the other posts, I’m afraid, it’s not really a review, more some scattered notes on how this story influenced the later series; so if you haven’t read the book then a) FFS, do, it’s brilliant, and b) what follows might be a bit baffling, sorry. Anyway, here we go.

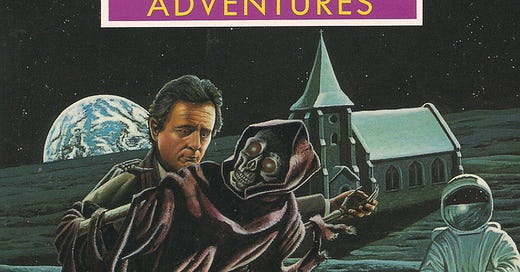

Timewyrm: Revelation

Published: December 1991

Read: February 2021

[About 100 pages in.] Okay, half time report.

I think this is probably the NA I’ve read most – this might be the fifth time – and I can never really keep a handle on the plot because it’s a) mental and b) not really that important.

I think what’s really new here is the sense of Doctor Who being a continuing narrative. All the Doctors have been to Cheldon Boniface [a village in which part of the novel is set]. Stuff that happened to earlier Doctors affects this one. He still grieves for Adric (and, more strangely, gives Katarina equal status, which implies he’s looked at a story table). He exists between the episodes we’ve seen, setting things up for them.

Basically, he and Ace are people.

It’s quite funny how crow-barred some of the contemporary references are (the first chapter is called “Step On”, ffs). Cornel correctly predicts that the Geldof girls will be famous, even if he picks the wrong one.

Moffat nicks bits of this for Death In Heaven I think. I like that the first Doctor fluffs his lines.

It is much easier to hear the actors speak the lines when you’ve only just stopped watching them.

[After I’d finished the book.]

Okay well obviously I knew this was massively influential but nonetheless the extent to which you can spot bits that the new series just lifted wholesale every dozen pages has thrown me. Ace’s imagined “nice” life is Donna in The Forest of the Dead. (The library might also be The Library though that’s probably pushing it a bit.) The church under siege is Father’s Day. The idea of being stalked by a monster formed of your own regrets, and the physical object that links a psychological realm to a real one, are both in Heaven Sent. Even the idea of the Doctor’s self-doubt being overcome by an expression of faith from a companion is there in Parting of the Ways (though that’s also Fenric, sort of). Oh, and at one point, there’s the line “Doctor, heal thyself”.

Gonna go out on a limb and guess that Moffat has read this more than once.

[So I suspect, has Chris Chibnall: the idea that past Doctors exist in some form on the current Doctor’s head, which is the big twist in The Power of the Doctor, is lifted from here, too.]

It’s even – this is a weirdly very Doctor Who thing – set a year in the future for literally no reason.

One odd thing about reading it now is that the fact it’s set in the Doctor’s mind is meant to be the big twist, roughly where the part three cliffhanger would go... but it’s both so key to the book and so obvious that I’d forgotten it was meant to be a surprise. I’m not sure you can read it as if you don’t know that.

The other thing that’s really impressive about this is the scale. There’s no pretence whatsoever that this is a novelisation of a TV story we didn’t see, it just doesn’t work like that. There are too many settings, too many effects, too many characters. I’m not even sure it’s a conscious decision, exactly, Cornell just automatically writes a novel, and doesn’t stop himself putting the first Doctor in it.

Some of it isn’t terribly subtle. The multiple inversions of “end my life”. Mother/maiden/crone. Dorothy following the yellow brick road. The fifth Doctor as Jesus, FFS. Do we know why the 2nd or 6th Doctors don’t put in an appearance, btw?

It’s sort of interesting how quickly the NAs become Cornell’s thing. He’s the first new writer to produce one, and his second is only five books later... By the point most of the other key writers of the period have even started pitching, Paul Cornell had set out an entire new mythology.

When I was a kid btw I found the spine colours of the NAs weirdly fascinating. Kept vaguely looking for patterns. Don’t know why.

Next time: former script editor Andrew Cartmel’s novel Cat’s Cradle: Warhead.

You’re right on the crowbarred references, but it’s entirely deliberate and one of those innovations that’s lost impact through familiarity since: the first time Who really existed as culturally contemporary (bar the odd Beatles reference in the 60s/70s), with references to the things 70s kids grew up with and watched/read/listened to. It’s the second big generational shift in Who writers, which we don’t quite acknowledge because it’s so close to the last one, and it’s a shift that lasts up to the Chibnall era.

Paul’s right that his later books are technically better, and he may well be right that Russell would’ve made all the same moves in 2005, but it certainly opened up the books as a distinctive flavour of Who and at least pointed the way to how the series could successfully be revived. Like all revolutionary works though, you maybe had to be there to get the full impact because so much of what it brought in is just the texture of the series these days.

My understanding is that there was a 6th Doctor / Valeyard section that PDE/Bex asked to be cut out.